Faster Python - Tips & Tricks

Introduction

There is a plethora of information about how to speed up Python code. Some stategies revolve around leveraging libraries like Cython whereas others propose a “do this, not that” coding approach. An example of the latter is using vectorized implementations instead of for loops. There exist many “do this, not that” strategies but I decided to focus on just a few, which I discovered in the Links section below.

My initital intent was just to test the assertions. However, as I collected experimental data on the various methods, I became curious about another claim I often hear: Python 3 is faster than Python 2. So I plied the exact same experimental methods in Python 2.7 (Py27) and Python 3.5 (Py35), affecting the necessary changes like using xrange for Py27 and and range for Py35. All of my experiments as well as timings and corresponding plots can be found here: Py27 Notebook and Py35 Notebook.

The plots contained in this article depict the results of my experiments for Python 3 and are labeled as such.

For detailed information including methodology and quantitative values for timings as well as details about Python 2, please review the notebooks linked above.

This post is split into two parts. In Part 1, I will compare two approaches commensurate with the “do this, not that” logic to see if there is a substantial difference and, if so, which approach is better. In Part 2, I will compare Python 2 and Python 3 to see if there is credence to the claim that Python 3 is indeed faster.

Part 1: Comparing Methods

In this part, I will describe and compare approaches for the following:

- Looping Over A Collection

- Looping Over A Collection & Indices

- Looping Over Two Collections

- Sorting Lists In Reverse Order

- Appending Strings

- Standard Library

- ListExp vs GenExp

- Dots

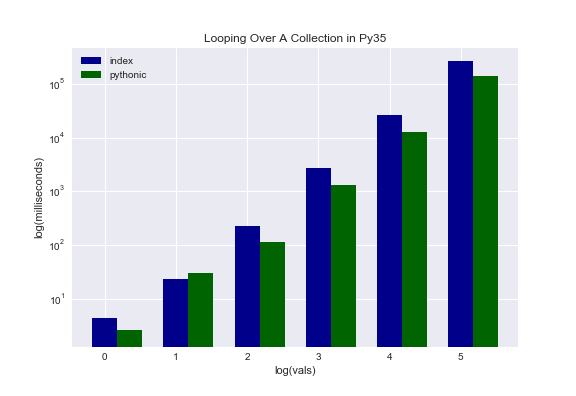

Looping Over A Collection

Looping over a collection is like this. Say you have a list of animals [‘aardvark’, ‘bee’, ‘cat’, ‘dog’] and you want to access each item one at a time. How can you do this? One way is to access the item by index. So, for example, you could use a listcomp like this:

animals = ['aardvark', 'bee', 'cat', 'dog']

[animals[i] for i in range(len(animals))]

Of course, this example is silly because we are generating a list from a list. However, the point is that we are iterating and doing something with the iterables. The thing we do can be anything.

Another way to approach the same problem is:

animals = ['aardvark', 'bee', 'cat', 'dog']

[animal for animal in animals]

It is definitely easier to read and understand what is happening. But is it faster? Turns out that it is. The second approach cuts the processing time nearly in half. Below is a plot depicting the difference.

Please note that this plot and all subsequent plots are log-log plots.

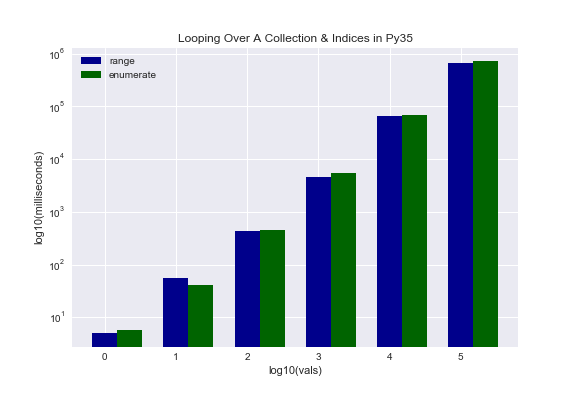

Looping Over A Collection & Indices

We know what looping over a collection looks like. What is this indices business that we’re now incorporating? Well, instead of just returning the list item, we also want to know its index value. The two approaches that were tested are as follows:

# Approach #1

animals = ['aardvark', 'bee', 'cat', 'dog']

[(i, animals[i]) for i in range(len(animals))]

# Approach #2

animals = ['aardvark', 'bee', 'cat', 'dog']

[(i, animals) for i in enumerate(animals)]

Again, the second approach is clearly more readable. But is it faster? Turns out the first approach tends to be slightly faster. Unfortunately, I am not entirely sure why this is the case. It is something I intend to investigate in the future.

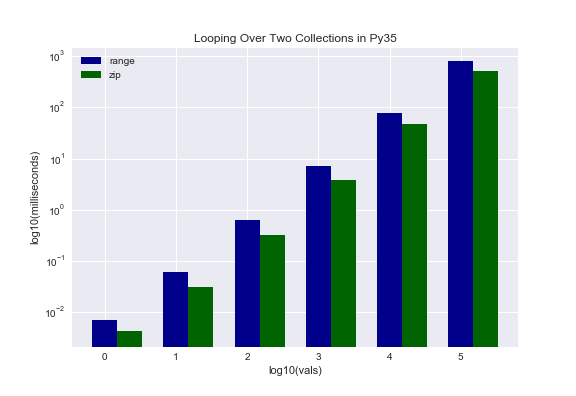

Looping Over Two Collections

We know what looping over a single collection looks like. What do we mean looping over two collections? Here’s an example. Say we have the animals list as before. Also say we have another list, of flowers this time: [‘allium’, ‘bellflower’, ‘crocus’, ‘dahlia’]. The output we are looking for is a list of tuples that looks like [(‘aardvark’, ‘allium’), (‘bee’, ‘bellflower’), (‘cat’, ‘crocus’), (‘dog’, ‘dahlia’)]. The two approaches tested are as follows:

Approach #1

animals = ['aardvark', 'bee', 'cat', 'dog']

flowers = ['allium', 'bellflower', 'crocus', 'dahlia']

[(animals[i], flowers[i]) for i in range(min(len(animals), len(flowers)))]

Approach #2

animals = ['aardvark', 'bee', 'cat', 'dog']

flowers = ['allium', 'bellflower', 'crocus', 'dahlia']

[(animal, flower) for animal, flower in zip(animals, flowers)]

I suspect most everyone would agree that the second approach is more Pythonic. But is it faster? Here we see our first discrepancy between Py27 and Py35. The first approach is faster for Py27 while the second approach is faster for Py35. The reason for this peculiar behavior has to do with the zip function. In Py35, zip() is an iterator whereas it is not in Py27. One way to combat this in Py27 is by using izip() in the itertools library. As an aside, if you are not famililar with itertools, it is definitely worth looking up. Essentially it is a library of iterables that can dramatically speed up legacy code.

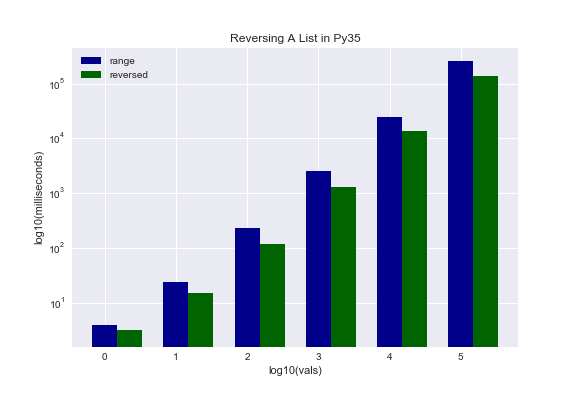

Sorting Lists In Reverse Order

This one is straightforward. Say I have my list of animals but I want to reverse the order so it looks like [‘dog’, ‘cat’, ‘bee’, ‘aardvark’]. Here are the two approaches:

Approach #1

animals = ['bee', 'dog', 'cat', 'aardvark']

[animals[i] for i in range(len(animals)-1, -1, -1)]

Approach #2

animals = ['bee', 'dog', 'cat', 'aardvark']

[animal for animal in reversed(animals)]

The second approach is once again much more elegant. But is it faster? Yes, it is. By quite a bit and for both versions of Python.

Appending Strings

Say I want to loop through and append my strings like I would a list. If you are familiar with Python strings, you know that a new string is created, not actually appended to the original string. Good to know if you did not already. So let’s look at the two approaches.

Approach #1

my_string = ""

mylist = list('abcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwxyz')

for item in mylist: my_string += item

Approach #2

my_string = ""

mylist = list('abcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwxyz')

my_string = "".join([item for item in mylist])

The first is probably easier to wrap your head around unless you have already worked with the esoteric looking string.join() function before. So which is faster? It appears the first approach may be faster. However, I am calling this result inconclusive. Why? I will skip the implementation details but the short version is that I was only able to time a single run for each approach using %time instead of the multi-run %timeit. Therefore, the results are questionable. I plan to circle back in the future to conduct a more thorough test.

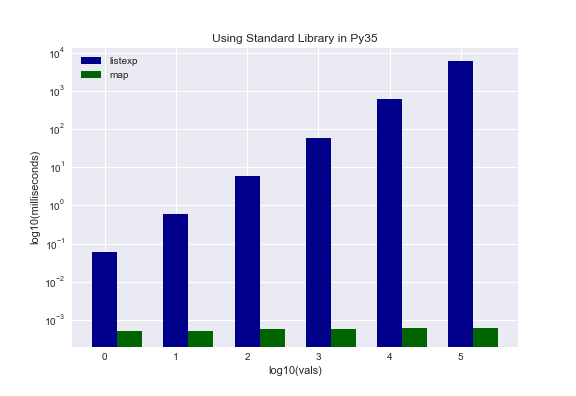

Standard Library

Python’s standard library is replete with built-in functions. The claim here is that these built-in functions are highly optimized and, therefore, significantly faster than a pure programming approach. In case that is not clear, let us look at a concrete example. Say I want to generate a list that stores the cumulative sum of consecutive integers. So if my set of integers is [0, 1, 2, 3], my generated list would be [0, 1, 3, 6]. Here are the two approaches that were tested.

Approach #1

newlist = [np.cumsum(item) for item in range(100)]

Approach #2

newlist = map(np.cumsum, range(100))

Which is faster? In this case, the second approach for both versions of Python is faster. An interesting result manifested, though. Here we see another discrepancy between Py27 and Py35. Py27 showed only slight improvement in the second approach, even as it scaled. However, Py35 not only ran much faster with approach two (nanoseconds instead of milliseconds or seconds), but scaled in constant time. That is a massive difference! There may be some credence to the claim that Python 3 is faster than Python 2 after all.

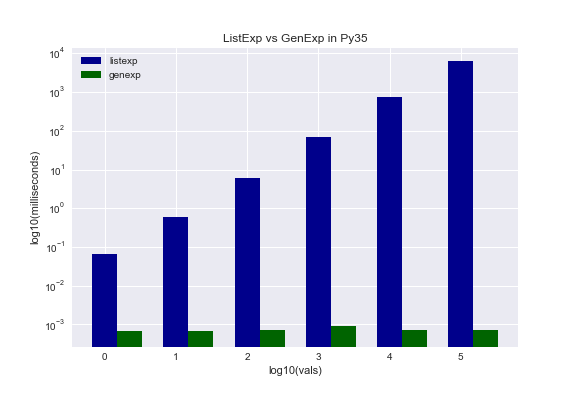

ListExp vs GenExp

I will assume you are familiar with list expressions (ListExp) at this point. Generator expressions (GenExp) may or may not be new to you. For an in-depth description, see this doc. One key quote from that doc is:

Generator expressions are a high performance, memory efficient generalization of list comprehensions.

The doc also goes on to say:

As data volumes grow larger, generator expressions tend to perform better [than list expressions] because they do not exhaust cache memory and they allow Python to re-use objects between iterations.

Let’s now test those assertions by leveraging the cumulative sum example from the last section.

Approach #1

[np.cumsum(item) for item in range(100)]

Approach #2

(np.cumsum(item) for item in range(100))

Generator expressions are certainly easy to use as they look almost identical to list expressions. So do they perform as touted? In both versions, the answer is unequivocally YES! List expressions scaled with the data whereas generator expressions scaled in constant time for both versions. An interesing result is that Py27 generator expressions were slightly faster than Py35. I am unclear as to why that is the case. Worth exploring in the future.

Update: Generator expressions seem to evaluate lazily, meaning they do nothing until you call for some action. This would explain why they seem to scale infinitely well. The big takeaway is generator expressions allow you to handle data that won’t fit into memory as well as an infinite stream of data. List expressions breakdown in both scenarios.

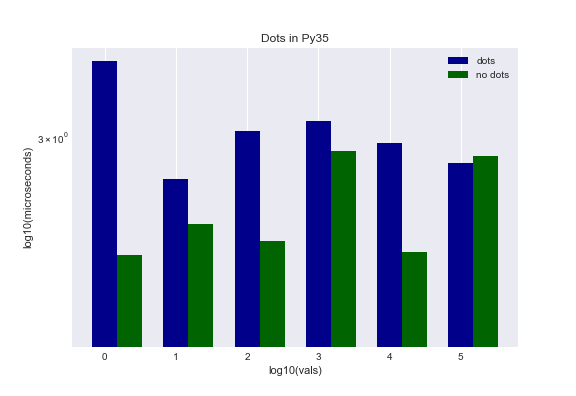

Dots

The final strategy that I tested had to do with this thing called dots. Dots is just another way to say methods. Lacking a clear way to state this strategy in words, I will instead get right to the approaches, which should be self-explanatory.

Approach #1

newlist = []

for val in vals:

newlist.append(np.cumsum(val))

Approach #2

newlist = []

cumsum = np.cumsum

append = newlist.append

for val in vals:

append(cumsum(val))

Was there a difference? Both Py27 and Py35 exhibited a marginal difference skewed towards the second approach being more performant. The evidence seems to indicate that there may be a minute performance gain but it hardly seems worth the effort given some of the dramatic results we saw in other categories.

Part 2: Python 2 vs Python 3

In the introduction, I presented a claim I often hear. Specifically, Python 3 is faster than Python 2.

First off, let me just say that while I gathered some empirical evidence by testing a few assertions, this small sampling of experiments is clearly insufficient to formally declare either way. That said, there was evidence that some of the inner workings of Python 3 are far more optimized and, therefore, Python 3 is faster in some regards. Take for example the standard library example using map(). We saw an enormous difference when comparing Py27 and Py35 where Py35 scaled in constant time and Py27 did not. In the Looping Over Two Collections test, Py35 also performed better because zip() is an iterator in Py35.

Summary

There are many ways to speed up Python code. Blazing fast libraries like Cython or Numba exist. However, I decided to focus on coding techniques in this article. As such, I identified a few techniques that looked promising and ran experiments to determine if the assertion that they lead to speedier code is in fact true. As an add-on, I wanted to explore the often asserted claim that Python 3 is faster than Python 2. Without further ado, here are the results in classic bullet point format:

- Avoid using a list’s index to access its items when looping over a collection

- Using enumerate() is more beautiful but not faster for looping over a collection and indices

- Mind your Python version when looping over two collections - use itertools for Python 2

- Use built-in functions whenever possible

- How you append strings may matter at scale but my experiment was inconclusive

- Forget list expressions at scale; rock generator expressions instead

- Dots may give you marginal performance gains but may not be worth the effort

- When Python 3 is better than Python 2, it is MUCH better

As a long time Python 2 user, this experiment got me much more excited about Python 3. Yes, I know Python 3 is the future but now I have something tangible to grasp on to - proof that aspects are indeed speedier and can lead to faster code. If nothing else, having conducted my own experiments has provided me the catalyst to finally make the transition.

In sum, this was a fun project that got me thinking. There are so many avenues left unexplored and this project raised many more questions than it answered for me, yet now I feel much more confident about the prowess of Python 3.

As always, I hope you found this enlightening, entertaining, or both. If you have questions, comments, or feedback, please let me know.

Links

4 Performance Optimization Tips For Faster Python Code

PythonSpeed Performance Tips

6 Python Performance Tips